Gyojung on making their first album 13 years after forming

Written by Ethan Kim (@count.kim)

Time moves strangely around Gyojung. Despite forming in 2012, the four-piece band has never been in a hurry to achieve anything, but their determination has only grown stronger with each passing year. The name Gyojung (교정) started as a small thing in common: all the members were wearing braces (치아 교정) at the time, and the word has a double meaning, referring both to orthodontics and to “correcting” something. Thirteen years later, the same idea of correction, adjustment, recalibration and rising again lies quietly behind their first full-length album, 망한현실 (Failed Reality), released on 10 December 2025.

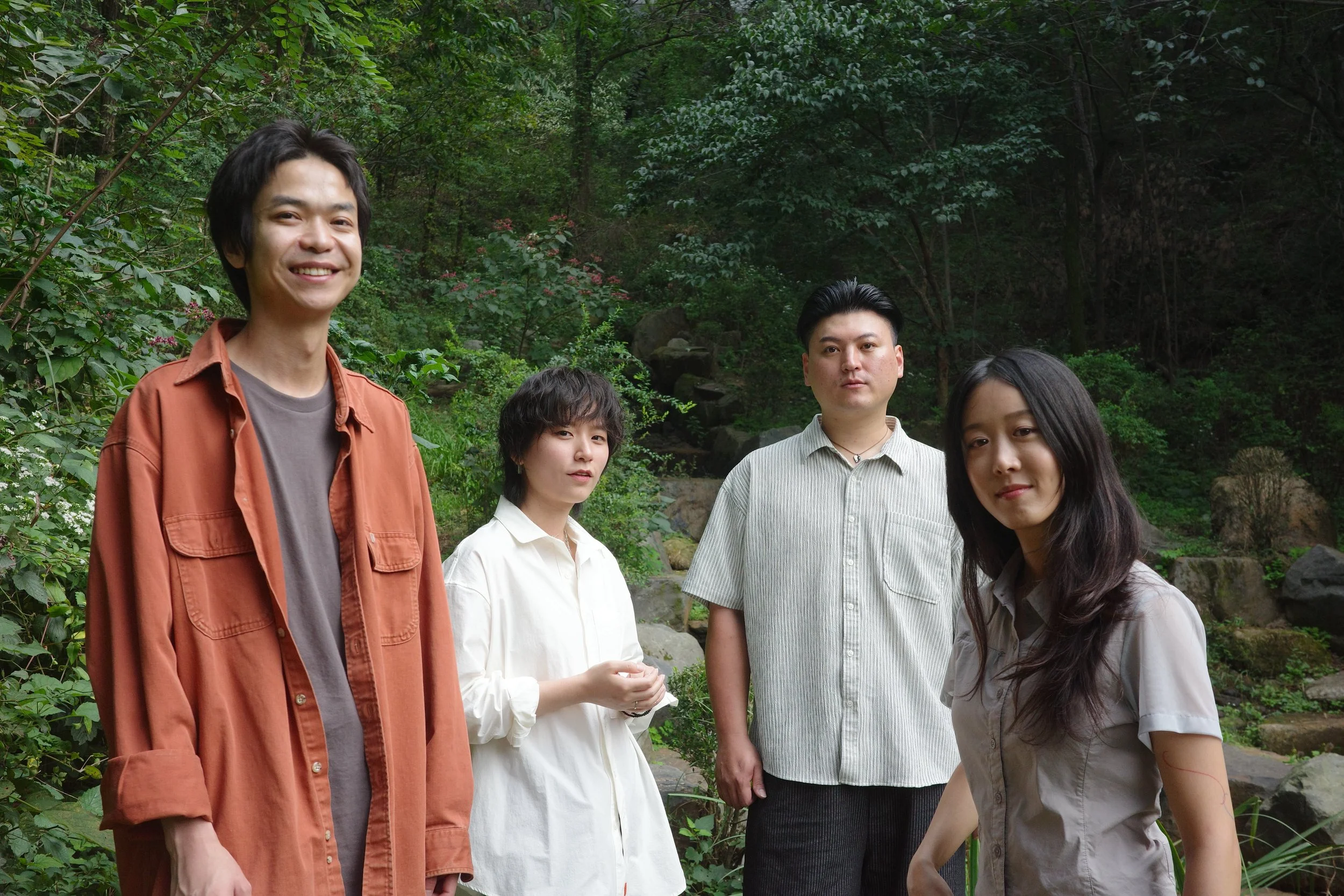

When I visit their studio to talk about the album, the atmosphere is warm and slightly chaotic: little jokes, familiar teasing, the kind of comfort that only comes when people have lived together for a long time. The members introduce themselves with the matter-of-fact clarity that characterises a band that has been a band for most of their adult lives: Shin Zaeeun (guitar), Kim Nahyeon (drums), Lee Kihak (vocals and bass) and Lee Taewook (guitar).

Gyojung had wanted to make an album for years, Kihak explains, but the plan was constantly postponed, scrapped, reformulated and pushed aside. At one point, when they were signed to Asia Records, they aimed to do a full-length then, too, only for the label to nudge them towards an EP instead. Later, they were told that singles were better for visibility, so the band did what many bands do: they continued to take one step at a time, release after release, without making a big deal out of the delay. Failed Reality is not so much a sudden breakthrough as a decision that was made quietly and finally brought to fruition.

The album's liner notes describe it as "the process of standing up again from a place that's already ruined," a phrase that sounds strange until you hear how Kihak talks about it. His conception of “destruction” is linked to disillusionment: the moment when one realises that the cultural figures one has been taught to admire are not always admirable, when one's perception of a stable “reality” collapses. Sometimes it's triggered by a scandal - a so-called legend accused of plagiarism, suddenly redefining the past. And sometimes it's slower and more inevitable: respected elders who age out of the present to death, like Jeon Yu-seong, Hermeto Pascoal and Ahn Sung-ki, passing from being “living references” to becoming traces in history.

Whilst Failed Reality is the band's forward-looking music, their 2025 EP 12'21 is a box of old photographs, made up of songs written between 2012 and around 2017. These tracks piled up during a period when Gyojung wrote constantly but didn't release much. They debated whether to keep those songs buried, worried they might feel dated, but eventually chose to reinterpret them with current ears. Even the title is a timestamp: in 2012, we were 21.

The album, Kihak insists, didn't take years of studio perfectionism. It came together relatively quickly, recorded not in a high-end studio but in their own practice room with their own microphones. At some point, the idea of doing things properly stopped feeling meaningful. They weren't interested in sanding down the rough edges or turning the mess into something prettified. There are moments, Kihak admits, where what he sings doesn't even match what's printed in the credits, because it didn't feel necessary to correct it.

This reluctance to polish themselves becomes part of the band's overall ethos. Kihak talks about survival in a way that feels deliberately unromantic: a mayfly may shine brightly for a while, but there's no guarantee of longevity. Some people disappear. Some are forgotten. In that context, it begins to feel like a form of survival to continue—steadily, stubbornly and without glamour.

The band's long timeline has still had clear turning points. Taewook said there's a sharp divide between pre-military service and post-military service, not just in scheduling realities but in how seriously they felt they were allowed to take themselves. Kihak agrees, adding that when they were younger, they sometimes turned down label offers because they were obsessed with perfection. Even their first EP on Asia Records took around two years to finalise under the weight of that pressure.

Now, the band's approach is looser, less fine dining and more eat the kimchi stew if it's in front of you. Kihak frames it as a kind of surrender that's also a freedom: if listeners don't like it, they don't like it. This is simply the kind of music Gyojung make.

The dynamism and ease that has been built up through long familiarity is evident right from the start of the album. The opening track, Too Comfortable (익숙함에 익숙해진), repeats a line that hits: now we have become accustomed to being “too accustomed” to it. When I ask if there's a specific moment when they remember becoming too accustomed to the familiarity, the answers come as affectionate complaints. Zaeeun says she's become accustomed to Taewook always being late. Nahyeon says she's become accustomed to Kihak's grumbling. Kihak says that after being together for so long, everything about each other feels familiar. Taewook adds that they understand each other so well now that there's almost nothing left that really makes them angry.

When I ask each member about their favourite song, their choices paint different angles of the same world. Zaeeun chooses the self-titled Failed Reality and praises its fast-paced, hyped-up energy. Nahyeon also mentions Failed Reality, but adds another choice: Never Ready for a Goodbye (큰 준비가 필요해), a song that feels different from the band's previous work—and where Zaeeun is the lead vocalist, giving it an unexpected emotional appeal. Kihak chooses In a PC Café in Busan (부산에서 PC방에간 이야기), partly because it's so ordinary: the band plays Crazy Arcade together, laughs and suddenly feels like teenagers again. PC bangs hardly change, even if your reflexes do. Taewook chooses the closing track, Closer (서로를 향한 모습), describing it as something that evokes a cosy winter image in his mind.

Their memories of the live scene in the 2020s are similarly mixed: joy, awkwardness and the feeling of returning to a place you once left. Taewook remembers Gyojung's first concert after the reunion on Channel 1969 as a strange feeling of returning to a job you were once fired from. For Kihak, last year's Zandari Festa stands out: they opened at Musinsa Garage Hall and arrived to a long queue outside, mainly for Lee Seungyoon later that evening, but still enough to spark something in their minds: let's show them what we can do. Nahyeon remembers their farewell party and release showcase on 31 December 2025, where Kihak repeatedly insisted that they should play “as if it were the last time” and work so hard that they were dripping with sweat. Zaeeun's most memorable experience was a cramped bar in Yeonnam-dong called Homeless Heaven, sometime around 2023, packed with people, where the audience was almost inside the performance - and Nahyeon's first show with the band.

Given the name Gyojung, it feels inevitable to ask what they'd most like to correct right now. Taewook answers bluntly: his weight. Zaeeun and Nahyeon both say posture—years of playing, they say, has a way of turning bad posture into actual pain. Kihak goes big: honestly, he says, it feels like the whole world needs correcting.

Outside the band, their lives remain busy in the way most long-running bands' lives are: multiple projects, overlapping timelines, the sense of identity never being just one thing. Kihak used to play in Goonam but has since left; he's currently active with his solo project USEDBOY and a band called Meotjinsaeng. Zaeeun plays in the girl punk band Sailor Honeymoon and also works solo. Taewook isn't involved in any other music projects right now. Nahyeon has mostly worked as a session drummer so far but says she expects to join a new band soon.

So how do they stay together for so long without becoming bitter and without the band becoming an obligation? Kihak describes it as a relationship: you're building something with people you didn't grow up with, which means you have to learn when to be considerate and when to ask for what you need. But he also believes that Gyojung are unusual because they don't micromanage each other musically. Instead of intense, technical demands, their language is more emotional and permissive: just do it; have fun; sing as if you're singing for yourself. He's seen bands with strict internal standards quickly fall apart, with relationships deteriorating under the pressure. In contrast, Gyojung feels like friends whose personalities complement each other—people who enjoy making music together and whose looseness has become their own concept.

That same looseness extends to how they want the record to be heard. Kihak says he sometimes sees comments online demanding a clear explanation - “what is this song trying to say?” - and the implication bothers him, as if lyrics must be spoon-fed like a report. Gyojung's songs are personal, he insists; they're closer to the private thoughts that rise up when life corners you into a situation.

Musically, this also explains why Failed Reality doesn't chase pristine sound. Kihak handled the mix himself and says he's grown bored of hi-fi: the band intentionally leaned lo-fi, not because uglier is automatically better but because chasing an ultra-polished sound can feel like cosmetic surgery—technically impressive, emotionally distancing. For mastering, they worked with Souichirou Nakamura, known for mastering Yura Yura Teikoku, because Kihak felt his sensibility would fit the record.

Even the album artwork carries that lived-in closeness. The cover, created by flashmo, depicts four figures meant to represent the members. Taewook identifies them: from the left, it's him, then Nahyeon, then Zaeeun, then Kihak.

As for the future, plans are concrete but not set in stone. They have a solo show in Seoul in February, then another in Busan at Ovantgarde in March. The Channel 1969 performance on 31 December was filmed in its entirety with a documentary approach. Depending on how the final edit turns out, they'd like to submit it to film festivals. Beyond that, they're undecided: maybe more singles, maybe another album that takes a year, maybe something else entirely. Gyojung has never been a band that plans the future within a fixed framework—they prefer to enjoy each moment as it comes.

Before I leave, Kihak offers a final message that feels less like a slogan than a personal ethic: "Use your imagination properly. And instead of always listening to other people's stories, try living as the main character in your own. If you do that," he says, "good days will come for everyone. And happy new year."