Bàn 半 Crew, intact, in Jeonju: The graffiti crew fighting to bring new colour to one of Korea's most traditional cities

Photos and words by Christian 이수 Mata

There are only 2 explicitly approved graffiti locations in Korea: Apgujeong Tunnel and Sinchon Tunnel, both located in Seoul. This August, it was announced that the Apgujeong Tunnel is being demolished with a projected completion date of June 2026, leaving Korea with only 1 legal graffiti zone. This might be confusing given how many prominent brands like Hyundai or K-pop idols like Karina or rappers like G-Dragon feature graffiti and "hip-hop" aesthetics. Outside of the upper echelons of stardom, it's easy to find hip-hop lounges around most cities, and streetwear is a common look among young people. But outside the metropolitan area of Seoul, the actual act of graffiti still exists underground.

Jeonju, the gastronomy capital of Korea, is often called "the most Korean city." Home to lots of traditional culture like the oft-filmed hanok village, hanji (한지) paper craft, traditional Korean liquor, and of course, the best Korean food. Just outside the restaurant walls littered with signatures and accolades, Jeonju has some exciting contemporary and alternative culture. There are DJs with roots in Jeonju (shout out to the Kimchi Factory Homies), b-boys, performance artists, tattooists, and more. While Jeonju is smaller and older than Seoul or Busan, there is still a growing push from Jeonju youth to host events that feature alternative culture like rock music, skateboarding, twerking, experimental art, etc. Among this young crowd is Bàn Crew (반,半).

Their name is a symbol of their camaraderie and continuing journey as artists. Bàn Crew consists of artist and CEO No Chae-rin (pictured left), fellow artist Kim Bo-yeon (pictured below), and manager and coordinator Hwang Geon-ha (who is on indefinite hiatus, taking care of other business). Bàn comes from the Chinese character meaning half (半), while their slogan "things that aren't intact" (不完全) continues this idea. One meaning for the name and slogan "is that when we are separate, we can't be complete or perfect, but working together, we can do anything."

The other meaning is simply meant to capture "something like our immature and imperfect youth," Chae-rin explains. The 2 artists both studied design before deciding to form a crew 3 years ago with their friend Geon-ha. They rely on each other to keep growing as graffiti artists and to support each other in a city, region, and country that is not yet open to graffiti.

Speaking on Korea's view of graffiti as a whole, the crew acknowledges that it's still something new for the country. Chae-rin remarks that there are "so many people who like or know about graffiti in Korea—I can feel that a lot while I do it, but there are not many places where you can experience it." But she thinks graffiti is on its way to being accepted by everyone because "there are a lot of cases where a subculture builds into a driving force until it becomes established as mainstream."

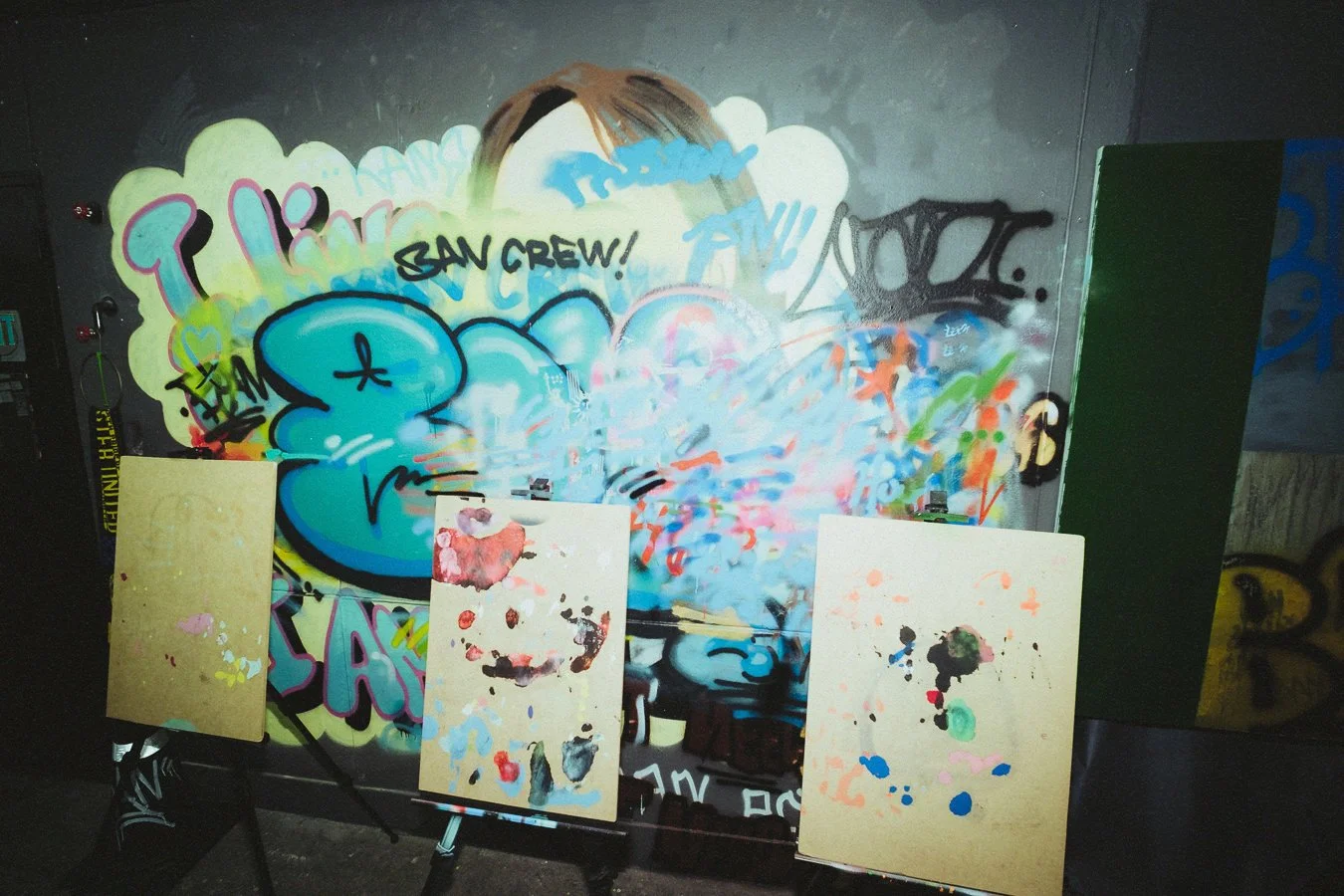

Though she admits that even now it's hard for graffiti artists to meet each other, Bàn Crew is determined to make connections in their region, seeking to collaborate with other fringe art initiatives like Urban Strikers or Stay Foolish. Working in Jeonju, the reactions to their work have already changed for the better. When working on events or putting up a wall piece, Bo-yeon finds that most people "look curious or interested, and some want to join in even." But in the early days of practising under bridges or on walls, they found their work greeted with quick erasure and prompt formal complaints. But that didn't slow them down.

Since their beginning, they have worked hard to get a foothold in Jeonju by working with many local businesses like popular cafes, Jeonbuk National University, and even city hall. They also get involved in local events like b-boy competitions, Urban Striker's Bold events, and various workshops. They cite all this support as a key factor in their success. Independently, they held exhibitions and last year they opened their own shop and studio. Through rigorous effort, they quickly established themselves as an important part of Jeonju's cultural landscape.

Despite being a newer crew on the scene, their fascination with graffiti and subculture goes much further back. As a child, Chae-rin was drawn to "skate culture and graffiti, because everyone looked so cool and brands like Thrasher and Supreme were everywhere." Bo-yeon similarly found herself fascinated by cartoons, especially Bart Simpson with his graffiti and skateboarding. At a young age, she dreamed of having a cruiser skateboard, so she saved up all her allowance and New Year's money to get her first board, and from there, she continued to collect these pieces of culture. During their university days, the 3 members wondered why Jeonju couldn't have graffiti like other cities, and they decided to make Jeonju the city they wanted to see.

Their beginnings in skateboarding, cartoons, and design led the crew to take an unconventional approach to graffiti. While they do murals, characters, stencils, etc., like other graffiti artists, they also design lots of other goods. They make flowerpots, toy cars, and other "kitsch" items. As a tribute to their love of skater culture, they even made a skatepark bowl that can be used for finger skateboards or as an ashtray. Part of this came from using what they studied, but it also springs from wanting to do something new and relevant in their graffiti work. If you look around Korea's hip-hop and graffiti scene, it's easy to see that most people prefer "wild style graffiti, and even though it looks cool and we like it, we didn't want to be just another artist who does wild style," Chae-rin confesses. But they both admit that they are still growing into their style, and some positive reactions from Jeonju's audience amount to seeing graffiti "as a performance rather than an art," which is a far cry from what they experience when visiting bigger cities.

Their work outside of Jeonju continues to inspire them. Bo-yeon affirms that staying up all night at Heat Up The Street (힛 업 더 스트릿, Incheon 2023) was the happiest day of her life. "Our bodies were tired to death, but we were too excited being surrounded by passion and other artists that loved graffiti like us," she beams. For Chae-rin, it was a bit more nerve-wracking because it was her first time driving, and she had to handle the wheel all night on their trip home. Still, the festival's energy is something that they hope to recreate in Jeonju someday by continuing to foster the graffiti scene here. Another landmark event for them was inviting Daegu-Seoul graffiti virtuoso Ppange to Jeonju. Together, they created a large exhibition full of huge murals at the youth village of Jeonju, located above Nambu, the famous traditional market. Working with Ppange was invigorating for them because they both aspire to have a confident and self-assured style like hers.

Their dreams as graffiti artists also set them apart from most. Pull up any major Korean graffiti design and they have something in common: much like store signs, slogans, and shirts, they are all in English. But "why are people always using English? Why can't we make a graffiti font for Hangeul?" Chae-rin asks with determination to change how people think of graffiti. Though both she and Bo-yeon can do similar forms of graffiti (characters, letters, murals), Chae-rin is more interested in transforming fonts and is set to take on Hangeul lettering. Bo-yeon, on the other hand, has her sights set firmly on 2 goals: more massive pieces and using a traditional Korean canvas. "Jeonju is a city of tradition," she asserts. "I want to bring the contemporary urban culture of graffiti to hanok." Both of their goals seek to bring their love of Korea's culture to the outside world.